Our new grant recipients are researching, among other things, microbes in bedrock, the cultural history of fish, and the relationship between nature and humans. We awarded funding for 37 projects that provide understanding and solutions to environmental challenges.

We received a total of 369 applications in the 2019 general call for grant applications. The applications reflected many of the themes present in public debate: young people’s climate activism, climate anxiety, and the role of grazers, soil and forests in climate change.

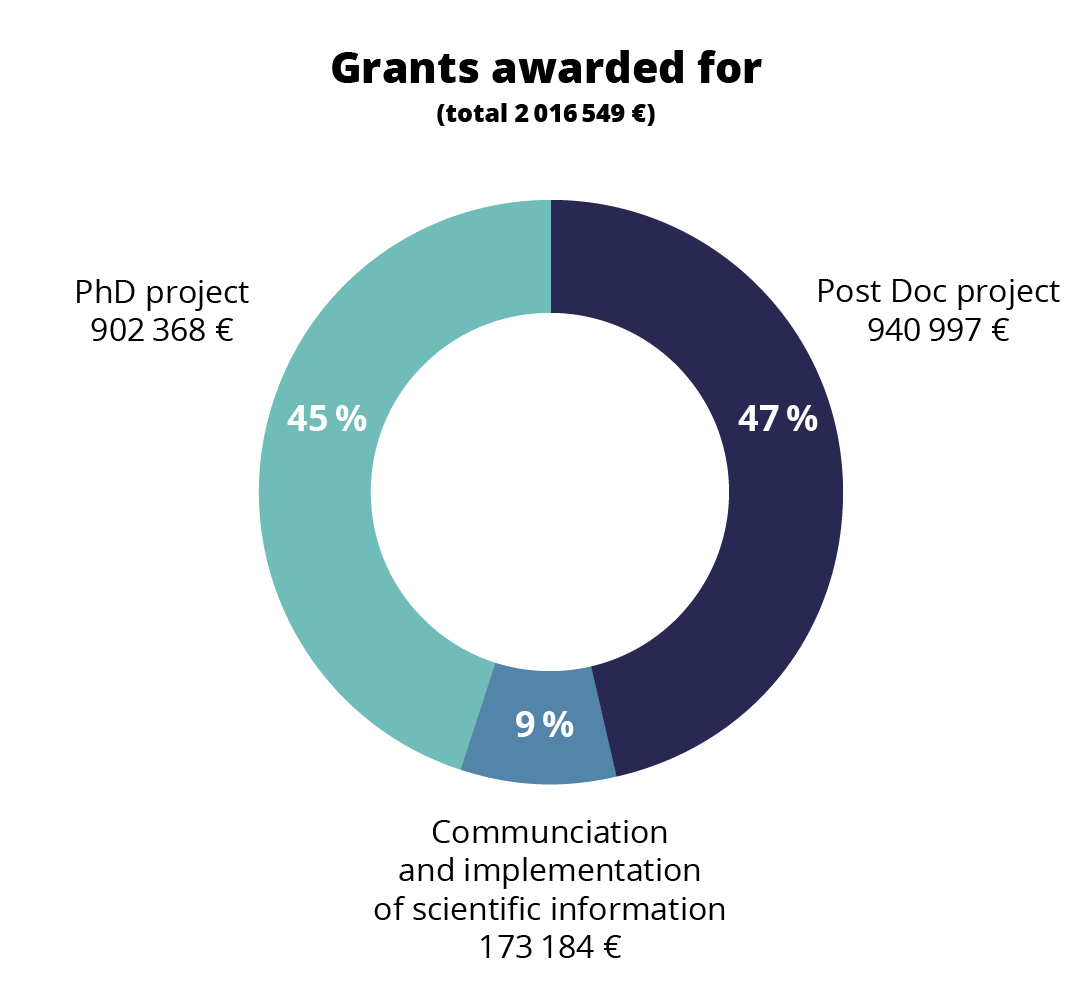

We awarded a total of about 2,200,000 euros in grants for 37 new projects. The aim of the projects is to find understanding and solutions for climate change, loss of biodiversity, the sustainability of natural resource use, water risks, and the chemicalisation and pollution of habitats.

Most of the funded projects were new doctoral or postdoc projects, which were funded for the duration of the whole project and for up to four years at a time. In addition to research work, we funded projects that communicate and implement researched environmental information into society.

In order to create solutions, it is important to understand both microscopic elements in nature and macro-level societal structures. Environmental challenges need acute solutions, but through research we are also finding hitherto unknown challenges and solutions to them.

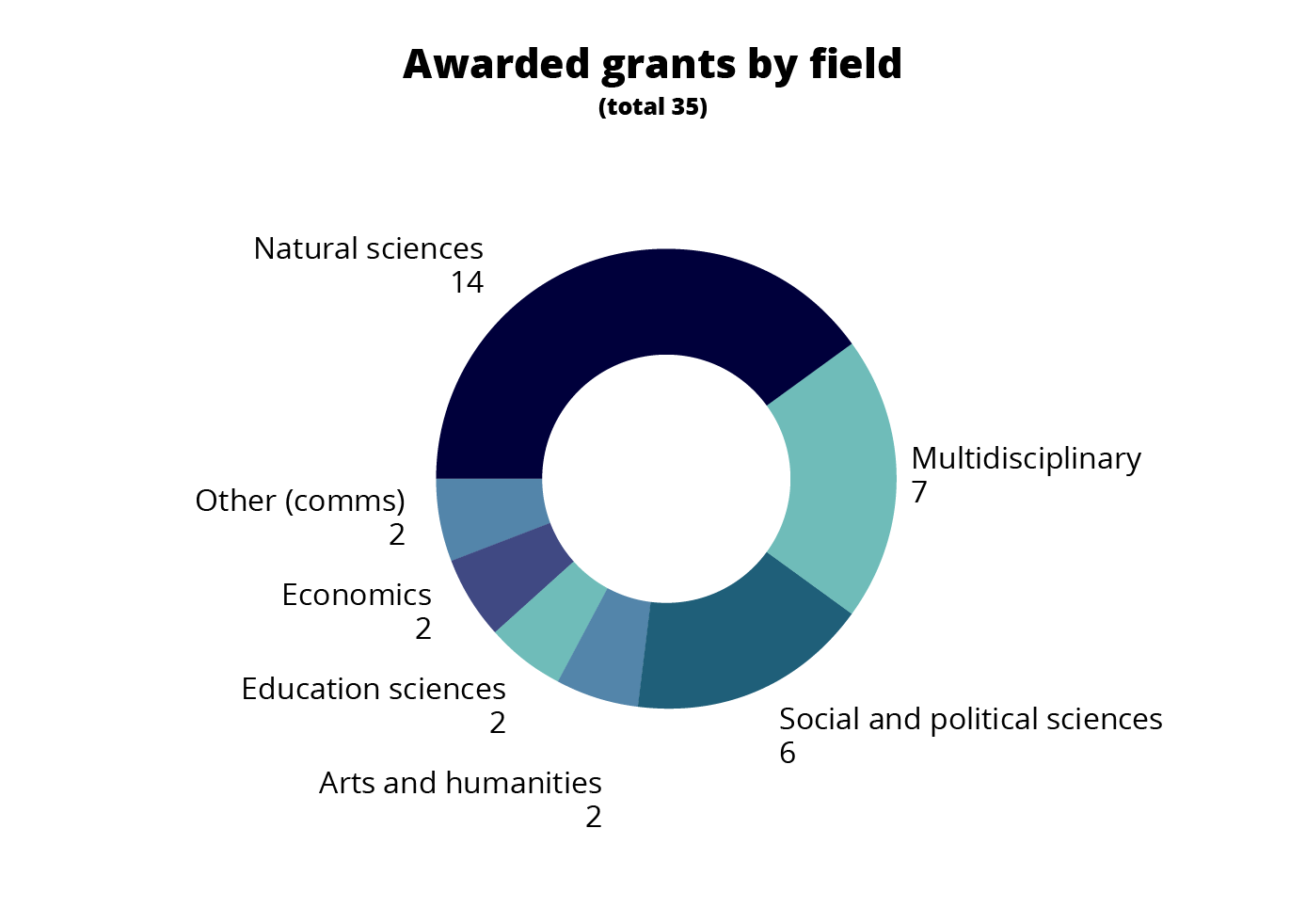

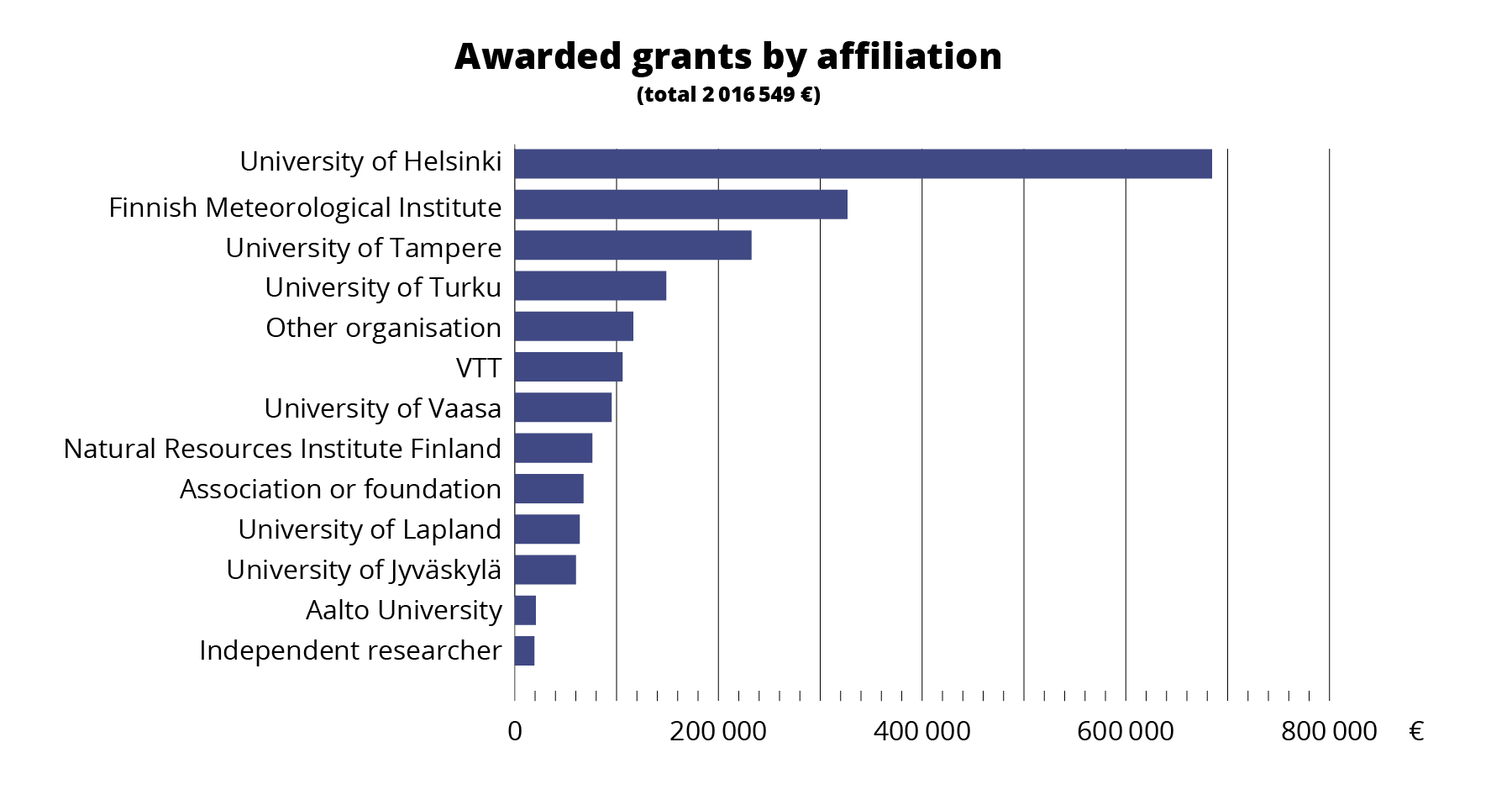

The funded projects demonstrate the broad spectrum of environmental research being conducted at various universities and research institutes in Finland, covering a wide range of scientific fields and approaches.

Read more about how projects are selected for funding.

Getting rid of anthropocentrism through empathy

In his research, doctoral researcher and non-fiction author Sami Keto is dismantling the invisible wall erected between humans and the rest of life.

“Even if we wanted not to, we can’t help but be members of ecological communities. Our body alone is an entire ecosystem. Our modern society has buried our ability to be connected to the rest of life”, Keto says.

By the rest of life, Keto means our entire biosphere from mammals to bacteria. Keto, who has a background in ecology, has previously studied the societal significance of empathy. According to Keto, a longer term solution to the ecocrisis is a profound cultural shift.

“Even in the midst of all our hurry, we have to find the patience to radically get to the root of the problem. Without it, we will only end up repeating the conception of reality that has led to the ecocrisis from the beginning.”

Could empathy help people encounter the rest of life? The concept of empathy is usually only linked to relationships between people, but Keto is exploring expanding the concept to also include the relationship between people and the rest of life. The project will create new methods for teaching empathy skills in schools, for example.

“Upbringing has a special role to play in bringing about cultural change.”

As-yet-unknown fungi live in the extreme conditions of deep bedrock

Despite the extreme conditions, numerous microbes live in bedrock several kilometres deep. VTT researcher Maija Nuppunen-Puputti studies the life of fungi and other microbes living in the deep biosphere.

“We don’t know much about the fungi and other microbes in bedrock yet, even though they make up a significant part of the Earth’s biomass. Various changes in the habitat, such as the release of gasses, activate the microbes and their metabolism forms compounds that can be either harmful or beneficial. The compounds formed can, for example, further the corrosion of metals or erode rock surfaces”, Nuppunen-Puputti says.

Changes in the habitat of deep biosphere microbes may increase as mining and bedrock extraction become more common. Some solutions to climate change may require deep drilling and building underground. A good example of this is the construction of geothermal power plants and tunnels.

“In Finland, nuclear waste will be disposed of in stable bedrock. It’s therefore important to understand what microbes as well as fungi do and produce in deep waters. Almost nothing is yet known about the activity of deep fungi, and my research is producing new information about them.”

Nuppunen-Puputti collects her samples from Outokumpu’s deep scientific hole, among other places, which extends up to 2.5 kilometres deep. Water samples are pumped from the deep hole, from which Nuppunen-Puputti plans to isolate and grow microbes in her laboratory. In the future, these microbes can be used to purify contaminated water, for example.

“There is a need for microbiological knowledge in society right now. Microbial interactions, geomicrobiological processes and understanding them play a key role in coming up with solutions to environmental challenges.”

The history of trash fish reveals forgotten food fish

Postdoctoral researcher Matti O. Hannikainen studies the use of fish as food and the factors that have influenced it in Finland from the 1930s to the 2010s.

“Some fish, such as salmon, have always been valued. Other fish species have been defined as trash fish. I’m studying how perceptions of the value and use of different fish species have changed and what factors have influenced these changes”, Hannikainen says.

According to Hannikainen, the 1930s in Finland were the golden age of fishing. Society was still largely agrarian and fish was part of many people’s diets. During the war, the purchasing of Baltic herring had to be rationed so that there was enough fish for everyone.

Since then, our society has become heavily urbanised and industrialised. Fishing is now quite a rare profession, although recreational fishing is popular. Nowadays, Finns prefer farmed salmon and other fish imported from abroad rather than, for example, domestic roach, bream or skipjack.

The popularity of some fish as food has led to overfishing of their stocks. Often a domestic species previously considered trash fish would be a more ecological option to eat.

“According to IPCC reports, it is precisely our dietary habits that need to change. Even though the choice feels like a small act in our daily lives, the impact multiplies with everyone making the same choice.”

Hannikainen had been mulling over the idea of the cultural history of fish species for several years.

“History won’t solve overfishing as an environmental problem. I hope, however, that my work will increase our understanding about this phenomenon and highlight the importance of partially forgotten fish species as local food.”

Take a look at all our funded projects here.